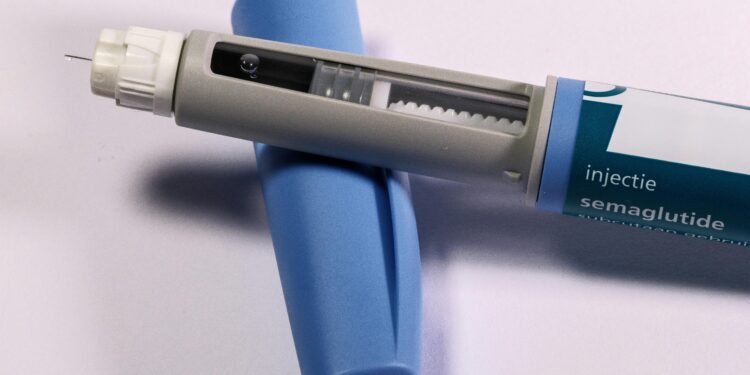

A prescription class once framed as a vanity shortcut has become a serious cardiometabolic instrument, and the public conversation still lags behind the clinical record. Searches for semaglutide and tirzepatide are rising because the drugs sit in plain view of everyday problems: weight gain, fatigue, hypertension, glucose drift, joint pain, sleep apnea, and the quiet dread of an avoidable myocardial infarction. When the SELECT cardiovascular outcomes trial reported fewer major cardiovascular events among people with overweight or obesity taking semaglutide, the story changed. Obesity became a cardiovascular risk management problem, with a weekly injection as an intervening tool rather than an aspirational slogan.

The clinical pivot: weight as a surrogate, events as the endpoint

For years, the strongest evidence for GLP-1 receptor agonists sat in glycemic control and weight reduction. That evidence is still central, but it no longer stands alone. In 2024, the FDA expanded Wegovy’s label to reduce the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events for adults with established cardiovascular disease and obesity or overweight, as described in the agency’s press announcement on the new indication. This is a doctrinal shift. It places obesity treatment on the same conceptual footing as statins and antihypertensives: long term risk reduction with measurable endpoints.

That shift also changes the burdens of proof expected by skeptics. A weight loss drug can be dismissed as cosmetic. A drug with outcomes data invites a more sober discussion: absolute risk reduction, adherence over years, adverse events, and access. The Wegovy prescribing information reads like chronic disease medicine because it is chronic disease medicine.

Mechanism is not destiny: what the biology explains and what it does not

GLP-1 agonists influence appetite, gastric emptying, and insulin secretion, and those effects translate into weight reduction for many patients. Yet a mechanism does not guarantee a uniform real world result. Patients differ in baseline metabolic rate, coexisting psychiatric medications, sleep patterns, food environment, and capacity to sustain follow up. In practice, the most important distinction is often operational rather than biochemical: whether a patient has structured monitoring, nutrition counseling, and a clinician who treats side effects as manageable rather than as moral failure.

Tirzepatide, with dual incretin activity, adds another dimension to the therapeutic landscape. Its approval for chronic weight management, described in the FDA’s Zepbound approval announcement, widened the market and intensified competitive pricing expectations. That competition matters because cost is the barrier that policy debates circle without resolving.

Safety and tolerance: the uncomfortable work of long term prescribing

The mainstream conversation treats GLP-1 medications as if side effects are incidental. Clinicians know otherwise. Nausea, constipation, diarrhea, reflux, and fatigue can shape adherence. More consequential questions remain under active study: pancreatitis risk signals, gallbladder disease, lean mass changes, and potential interactions with other long term therapies. The correct stance is neither alarmism nor complacency. It is clinical humility paired with structured monitoring.

The safety question also includes the ecosystem around the drugs. Shortages pushed patients toward compounded products and informal supply channels. As supply stabilized, regulators tightened posture. The FDA’s update on compounding policy during GLP-1 supply stabilization, including the agency’s determination about tirzepatide shortage status, illustrates how quickly the boundary between access and safety can move, as detailed in the FDA’s compounding policy clarification. Patients, often acting rationally in response to unmet need, may still end up exposed to variable quality inputs when policy and supply do not align.

Coverage is the real clinical endpoint

A medication can be evidence-based and functionally unavailable. That is the present reality for many patients. Medicare’s framework has historically constrained coverage of anti-obesity drugs, even as GLP-1s have been covered for diabetes and certain cardiovascular indications. A clear overview of the statutory and benefit design terrain appears in the Congressional Research Service brief on Medicare coverage of GLP-1 drugs. The result is an uneven map where indication, coding, and plan design decide access more often than physiology does.

Commercial payers and employers are recalibrating in public. The 2025 KFF employer benefits survey found increased coverage among the largest firms, with a parallel concern about cost impact on drug spending, summarized in KFF’s 2025 Employer Health Benefits Survey and the companion analysis on employer perspectives on GLP-1 coverage. Employers are experimenting with prior authorization, step therapy, and continuation criteria that essentially transform weight loss into a compliance contract. The ethical question is direct: when the standard of care becomes conditional on administrative thresholds, who bears the moral burden of denial.

Medicaid policy is similarly fragmented. KFF’s January 2026 assessment of Medicaid coverage and spending on GLP-1s shows limited coverage for obesity indications, even as demand rises and clinical guidelines evolve. The politics of obesity remain embedded in benefit design.

Clinical practice is being reorganized around a weekly injection

Even in clinics that do not prescribe GLP-1s, the drugs are changing patient expectations. Patients arrive with prior authorization letters, TikTok narratives, and questions about compounding. Clinicians must now practice “coverage literacy” as part of care. That means understanding formularies, documenting comorbidities carefully, and preparing patients for denials. It also means addressing a quieter issue: discontinuation. Weight regain after stopping GLP-1 therapy is common in clinical experience and supported by trial follow up patterns. Long term use raises the question of sustainability, both biologically and financially.

A mature clinical approach treats these medications as part of an integrated cardiometabolic program. That program includes nutrition planning, resistance training to preserve lean mass, sleep evaluation, and medication reconciliation. It also includes direct discussion about expectations. Some patients expect a simple, linear decline in weight. Many will have plateaus. A clinical relationship that normalizes those plateaus can prevent risky dose escalation or unsupervised sourcing.

The next phase: evidence will expand, and the politics will harden

GLP-1s are now embedded in broader questions about health system allocation. If outcomes benefits hold across larger populations and longer durations, the argument for coverage will strengthen. If adverse effects, discontinuation rates, or downstream spending rises, payers will push back. The public, meanwhile, will continue to talk in the language of individual responsibility because that language feels familiar. Medicine will continue to talk in the language of risk reduction because that language matches the data.

The decisive question is practical. A therapy with cardiovascular outcomes evidence will either become widely accessible, or it will become another marker of inequality, with access tracked to employer size, state Medicaid policy, and personal liquidity. The pharmacology is impressive. The policy architecture remains the limiting reagent.

What patients and clinicians can do now

Clinicians can anchor conversations in outcomes evidence rather than aesthetics. Patients can ask for explicit monitoring plans and side effect management strategies, and they can insist that prior authorization documentation reflect comorbidities accurately. Health systems can build workflow support that treats obesity as chronic disease rather than as elective care. Policymakers can decide whether cardiometabolic risk reduction is a public good, or a purchasable privilege.

A decade from now, the most telling part of the GLP-1 story may not be the molecules. It may be the paperwork.